JACOB ALAN COOK | DECEMBER 22, 2021

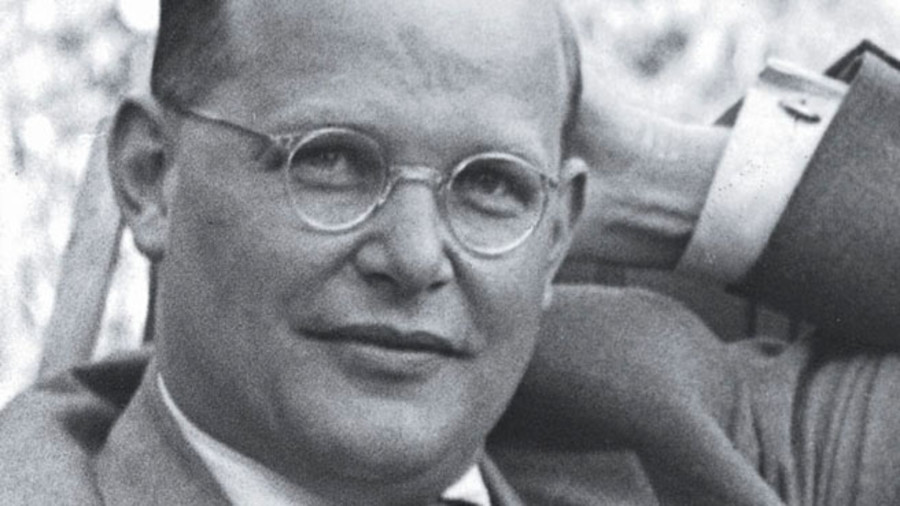

After his second visit to New York in 1939, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrestled with the character of Protestant churches in America versus those in Europe in an essay titled “Protestantism without Reformation.”

Even as he introduced his argument, which plays up history, sociology and political analysis for understanding the American church, Bonhoeffer offered some words of caution about using these modes. He expressed concern about balkanizing the global church, failing to see the single, shared office of God’s church in the world, and neglecting the real value of concrete church-communities that differ from our own. And I share these concerns.

As Bonhoeffer demonstrated, however, these fields of study can help us understand important dynamics in a clearly diverse and divided church landscape. With special reference to U.S. history, he keyed on how a land that never has seen the church unified (in confession or institutional forms) thinks differently from the start about what “the church” even is.

Origins of American church

European Protestants set out to make colonies in America as they fled, voluntarily or involuntarily, from religious battles. Among the Christians who remained in Europe, the unity of the church was remembered and presupposed. So, European Protestant energy was channeled into efforts to reform the whole church, which provoked charges of heresy, real fights and other coercive attempts to bring others to “the light.”

But the origin of the American church — already diverse in confession and existing as numerous refugee communities — engendered a spirit of toleration and manifested in formal protections of religious freedom. Over time, numerous denominations formed, split and merged as free, voluntary associations of local churches with common polity and practices. And when Bonhoeffer visited America, ecumenical organizations also had been forming, on the assumption of tolerance around confessional issues even while searching for united fronts on practical matters.

In his essay, Bonhoeffer pointed up these details to explain why Christians in America might see church unity as a goal (however remote) even if few could see any reason to think there was one church-community in America — let alone feel the fight to reform the whole. Starting from within this situation, now as then, one cannot help but see variety in the U.S. church scene and puzzle at claims to represent the one, true church.

Today I will argue that the postwar evangelical movement has reshaped this picture in the U.S., generating a new way of conceiving the whole and resuscitating the will to fight for it. Specifically, I will highlight how the biblical worldview concept has enabled visible leaders of this movement to capitalize on the individualism of American culture and raise a new, ostensibly conservative standard in American public life. This move has amplified cultural divisions and damaged many Christians’ understanding of the church and its mission, so the conclusion of this essay will point toward a more promising picture of church-community for transforming the heart of these conflicts.

“The biblical worldview concept has enabled visible leaders of this movement to capitalize on the individualism of American culture and raise a new, ostensibly conservative standard in American public life.”

Within nine years of Bonhoeffer’s essay (but to be clear, with no reference to it), Harold Ockenga described what he understood as “the New Reformation” unfolding in the neo-evangelical movement. Reading these two pieces back-to-back is fascinating, not least because the first pushes us to ask: What did Ockenga imagine as the target of his reformation?

Harold Ockenga preaching

Ockenga opened his essay with a stylized account of the Protestant Reformation and the historical conditions that preceded it, including the charge that the Roman Catholic Church had not allowed, and thus not benefitted from, the kind of competition that stimulates growth. The way he told the story, the whole Reformation hinged on the Bible’s liberation from human traditions into the hands of the people. A quote might help us catch the flavor of his commentary:

The Bible revealed to the people what was wrong with the church, namely, how far it had deflected from biblical teaching. Once the people began to read the Bible, they immediately recognized the distance which the church had departed from primitive Christianity in simplicity, sacrifice, and service.

In Ockenga’s view, greater “knowledge of the Bible incited the people to discussions of principles involved in Christianity.”

A liberated Bible?

Hiding here is more of the historical reality. Rhetorically, we might like to say the liberated Bible freed the people; but, in real time, literacy rates were very low, and new expositions, interpretations and emphases were circulated in two stages — pamphlets for the readers and oral accounts for the rest, between pulpit and pub.

What exactly it means for the Bible to be liberated from tradition is, in itself, an important point of conversation. Sola scriptura is lauded as one of the primary doctrines of the Reformation. On this point, Ockenga highlighted “the authority of the Bible alone uninterpreted by traditions.” And he went on to describe the Bible’s authority as “over against the authority of the church or of reason or of experience or of the inner spirit.”

While I am interested in defending this second notion, I am concerned about the way it bumps up against the first. Getting our view of Scripture right means opening ourselves to ongoing criticism because the most important meaning of Bible freedom is found in its own freedom from us. The Bible can only be for us and with us, as human beings seeking God’s face, if we honor the reality that it stands over against us.

“The Bible can only be for us and with us, as human beings seeking God’s face, if we honor the reality that it stands over against us.”

But all too often, American evangelicals have extended the authority of the Bible — as we might imagine it standing on its own, liberated from human traditions — to their translations and interpretations of that Bible. When they are our correct interpretations, we simply call them “expositions.” Hold onto this thought.

A ‘biblical’ worldview

Surveying the American social landscape in light of the primary Reformation doctrines, Ockenga was concerned with the fruits of mainline theology and social action. He saw the liberals running off course starting with contesting the Bible’s authority. They ended up following the course of modern secular folks, enthralled by the prevailing progressivism and theologizing the kingdom of God in terms borrowed from culture. The result was, in Ockenga’s view, not only disunited in effect but, more importantly, unbiblical and pernicious.

Fuller Seminary’s founding faculty: Harold John Ockenga, Wilbur M. Smith, Carl F.H. Henry, Harold Lindsell, Everett Harrison.

So, we return to ask: What did Ockenga imagine as the target of his reformation? Neither a new institutional unity (like a denomination) nor a new confession was Ockenga’s desired product — America already had too many. Rather, the New Reformation would materialize in individual Christians and some local churches taking up their intellectual starting point in the biblical worldview, embracing its supernatural elements. From there, the rest would follow much like it did in his reading of the 16th century Reformation.

Unpacking “the challenge to individual believers,” Ockenga emphasized “biblical action to fulfill God’s program.” He outlined four priorities with an intentional order: foreign mission, personal evangelism, education under a powerful expositor of the Bible, and only then social engagement in loving service and political activism. The order of the last two elements implicitly continued Ockenga’s criticism of progressive Protestants, who got the order wrong and read their Bibles through their social context and political goals.

Speaking for his own church, Ockenga assured the reader that evangelicals do not withdraw from cultural discipleship. “We … make our voice heard on all these matters of civic and legislative affairs.” And, moreover, he concluded his article with an appeal to the Reformation leaders of yore, who “would tell us that we must meet the challenge of our day for the sake of Christ … by fearlessly applying Christian truth to situations, and by sincerely carrying through to a logical conclusion these principles which we find in the Word of God.”

“Ockenga issued an invitation to join in the wish-dream of unity under a plain biblical worldview.”

To the many individuals dissatisfied with their own local church-communities, Ockenga issued an invitation to join in the wish-dream of unity under a plain biblical worldview. And he suggested they be prepared to sacrifice other loyalties and particular commitments when necessary to support this vision. The effects included weakening local ecclesial ties, engendering suspicion of real-world church-community, and underwriting libertarian, free-enterprising views of moral individuals in unvoiced multitudes.

Evangelical entrepreneurship

What neo-evangelical leaders aimed to “reform” was first the minds of individual believers. Ockenga’s vision for an evangelical Reformation cut across denominational lines to recover a unifying spirit. He decentered forms of religion and played up the feelings of common cause and core values at stake.

Focused as they were on individuals, early leaders did not anticipate strictly man-to-man operations so much as they imagined their audience to a silent majority of individuals. And even as they cast a “conservative” vision, they sought progress in the form of new associations, educational institutions, media outlets and the like. This stream of American evangelicalism always has been, as George Marsden famously observed, an entrepreneurial endeavor.

As Americans know well, entrepreneurship is inextricably linked with the free market virtue of competition. Ockenga explicitly made this link while criticizing the “monopolistic” Roman Catholic Church of the pre-Reformation era.

Churches often tailor worship to attract Millennials. That can be insulting to Millennials. (Photo/Catholic Archdiocese of Boston/Creative Commons)

When competing in a free and open market, success is measured by the literal, ongoing buy-in of everyday folks, who vote with their feet and their wallets. Thus, for decades pastors and consultants have talked about churches, particularly in densely populated areas, in terms of a marketplace. And on the supply side, evangelicals see few barriers to “church shopping,” whether moving to a new town or just growing wary of their local church’s message.

Moving in a slightly different direction, we can see how thought leaders, not least in evangelical circles, are platformed and canceled based on market dynamics more than movements of the Holy Spirit. Leaders are free and unconstrained as they attempt to gain ground or throw their weight around with appeals to an idealized worldview and its commonsense applications. And popularity and public opinion matter more than a fair amount in who gets to use such rhetoric and feel successful doing it, on whom the burdens of proof rest, and who gets to dismiss whom out of hand.

We need not read all this cynically. Competition and entrepreneurial endeavors are descriptively in the warp and woof of American evangelicalism. That fact does not mean everyone with a platform is merely self-interested or power-hungry or that no one really cares about what the Bible says. But to those who would see the biblical truth, as they have “exposited” it, shape more minds and cover more territory within their imagined audience of individuals — even to the end of a global reformation — temptations are prowling around like a roaring lion.

Market dynamics and moral outcomes

It is axiomatic that market dynamics are not always the best motivator or determiner of moral outcomes. For those who like an example, large numbers of followers, whether online or in the pews, can lend voice and influence to leaders with significant defects of character and judgment. This is one lesson from the popular “Rise and Fall of Mars Hill” podcast. But this is also how postwar American evangelicalism rolled onto the scene covered in unspoken assumptions based in worldly categories (history, sociality, politics) and not the Bible itself — even if visible leaders defended these ideas as if they were merely the biblical worldview.

For another example, we might consider the current data on how multiracial churches do (and do not) improve the overall problem unfolding in this series. This picture is coming through in books like Korie Edwards’ The Elusive Dream, numerous articles and reports on the most recent wave of the National Congregations Study. Citing these sources, Kevin Dougherty, Mark Chaves and Michael Emerson conclude that, for too many white Christians, “diversity is pursued by trying to attract people of color who will not challenge white congregants’ views and practices.” This is another feature of market dynamics even if, in many cases (although not all), problems arise contrary to the best intentions of leaders and participants.

Recalling Bonhoeffer’s comparison of the fight or flight activity of European and American Protestants, we might observe that neo-evangelicals reintroduced a “fight for the whole” mentality in the U.S. context — but in a different mode. Reconceiving U.S. history as a triumph of evangelical influence that had since waned, Ockenga framed his reformation as an attempt to recover this ideal, but non-existent, American church.

“The entrepreneurial, market-share competition for individuals’ attention and loyalty, in effect if not intention, defines the perpetual struggle for an evangelical identity.”

With no structures to fight or resist except those already deemed apostate, Ockenga and company could cast themselves as conservatives even as they created new institutions (a progressive act). And the whole project could be pursued with reference to a world-viewing population of individuals with personal knowledge of the liberated Bible and its application, standing in for “the church.”

For the rest of the post…

Recent Comments