You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Maria von Wedemeyer’ category.

by Brian Rosner

I started 2020 with five New Year’s resolutions and seven anticipations, things I was eagerly looking forward to, such as special social occasions and travel. I won’t comment on my progress on the resolutions — my brother-in-law reckons New Year’s resolutions are a to-do list for the first week in January, and I don’t want to confirm his cynicism. But I will report that five of my seven anticipations have been canceled, with the two in November and December looking less likely every day.

For some of us, the personal cost of the coronavirus will be huge; for others less profound, but still troubling. But one form of suffering will afflict us all — namely, the experience of disappointment. With everything from meals out and sport to weddings and funerals being canceled, “cancel culture” is taking on a new meaning. No one will be immune from disappointments, the displeasure of having our anticipations unfulfilled.

For a case study in coping with disappointment in the context of isolation and social distancing, we find a surprising source of help in Dietrich Bonhoeffer — the pastor, author and church leader who was active in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s.

With the rise to power of Hitler in 1933, Bonhoeffer’s fairy tale took a dangerous turn, transforming into a spy thriller. His opposition to National Socialism began early, when Bonhoeffer gave a radio broadcast on the dangers of charismatic leadership. It was abruptly ended by government censure. For the next ten years, Bonhoeffer worked for the good of his nation, eventually operating as a double agent. Employed by the Abwehr, a division of German Intelligence, Bonhoeffer used his contacts outside of Germany to support the insurgency. A man of impeccable integrity, Bonhoeffer also functioned as the conscience of the conspirators, commending their moral courage and bolstering their resolve.

Along with the spy thriller, Bonhoeffer’s life was a tragic love story. In June 1942 Dietrich met Maria von Wedemeyer. Maria was beautiful, poised, cultured and filled with vitality, but only eighteen years of age — fully seventeen years younger than Dietrich. Bonhoeffer and Maria fell in love. Maria’s father had been killed on the Russian Front and her mother insisted on a year’s separation to test the couple’s feelings. But Maria convinced her mother otherwise and in January 1943, with some restrictions in place, they were engaged to be married. Unfortunately, “happily ever after” is not the way their story ended.

Two key aspirations of Bonhoeffer’s life — the renewal of the German church and people and his plans to marry his fiancée Maria von Wedemeyer — were both cruelly thwarted. In 1943 he was arrested by the Gestapo, incarcerated for two years, and finally executed at the order of Adolf Hitler.

If some disappointments are mild, Bonhoeffer’s were crushing. How did Bonhoeffer handle his disappointments? Although he wrote a number of books, the answer to this question is found in the remarkable letters to and from his parents, relatives, fiancée and above all his best friend Eberhard Bethge, collected and published in the now classic volumes Letters and Papers from Prison and Love Letters from Cell 92. With social isolation ahead for all of us, at least in a physical sense, Bonhoeffer’s prison musings offer sage advice and salient lessons.

First, focus on what really matters. According to Bonhoeffer not all disappointments are equal. He urged an ordering of priorities:

There is hardly anything that can make you happier than to feel that you count for something with other people. What matters here is not numbers, but intensity. In the long run, human relationships are the most important thing in life. God uses us in his dealings with others. Everything else is very close to hubris.

In the strange world of physical distancing, we do well to remember that we don’t have to be relationally distant. There are still ways to cultivate community that don’t involve getting up close and personal physically.

Second, stay cheerful. Bonhoeffer wrote to his fiancée Maria: “Go on being cheerful, patient and brave.” And he told Bethge to “spread hilaritas.” Even amid hardship, a joyful optimism can prevail. Cheerfulness was in fact one of Bonhoeffer’s abiding qualities despite the horrors of prison. In his famous prison poem, “Who am I?” the opening stanza reads: “They often tell me I would step from my cell’s confinement calmly, cheerfully, firmly, like a squire from his country-house.”

Indeed, Bonhoeffer’s letters from prison are surprisingly dotted with glimpses of humour. He quips: “Prison life brings home to one how nature carries on uninterruptedly its quiet, open life, and it gives one quite a special, perhaps a sentimental, attitude towards animal and plant life, except that my attitude towards the flies in my cell remains very unsentimental.” Bonhoeffer and Bethge wrote back and forth over the naming of Bethge’s first child. When the name “Dietrich” was floated, Dietrich wrote back to the couple amusingly: “You still seem to be thinking of ‘Dietrich’. The name is good, the model less so.”

Perhaps those corny coronavirus memes scattered across social media serve a purpose. In Bonhoeffer’s case cheerfulness was no accident of temperament; it was born of his unshakeable confidence in God: “I’m travelling with gratitude and cheerfulness along the road where I’m being led. My past life is brim-full of God’s goodness, and my sins are covered by the forgiving love of Christ crucified.”

Third, embrace optimism. Bonhoeffer’s approach to prison life was not to allow the confinement to restrict his activity. Quite literally, he did not sit still while waiting for his hope for freedom to materialize:

I read, meditate, write, pace up and down my cell — without rubbing myself sore against the walls like a polar bear. The great thing is to stick to what one still has and can do — there is still plenty left — and not to be dominated by the thought of what one cannot do, and the feelings of resentment and discontent.

This is good advice for anyone facing the frustrations of an ongoing disappointment and restrictive circumstances.

Lutheran pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed by hanging, at age 39, in a Nazi concentration camp in 1945. He and a small but fierce contingent of devoted Protestants actively resisted the Nazi encroachment on both church and state.

His writings have influenced subsequent generations who struggle with the role of Christian devotion in a hostile culture. “The Cost of Discipleship,” a modern classic, is widely known for Bonhoeffer’s haunting statement: “When Christ calls a man, He bids him to come and die.”

“When Christ calls a man, He bids him to come and die.”

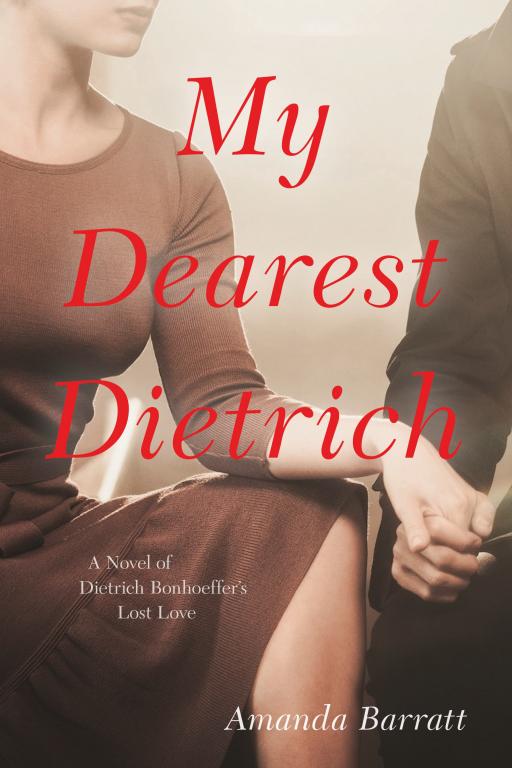

What is not as readily known is that he possessed an amorous side, loving a woman named Maria von Wedemeyer to whom he became engaged in January 1943, when Bonhoeffer was 36 years old (and von Wedemeyer 18). He would be arrested by the Gestapo three months later.

During the two short years of his engagement to von Wedemeyer, and what ended up being the last two years of his life (1943-1945), the two exchanged letters that were both amorous and wrenching. Published for the first time in 1995 as “Love Letters from Cell 92” and edited by Ruth-Alice von Bismarck and Ulrich Kabitz (Abingdon), this intimate correspondence revealed a side of Bonhoeffer that is generally not known:

“Wait with me, I beg you! Let me embrace you long and tenderly, let me kiss you and love you and stroke the sorrow from your brow.”

The reader also knows the tragic ending to this tale, while the writers themselves do not. (Bonhoeffer would be executed in April 1945, only weeks before Hitler killed himself and the Germans surrendered.) A constant theme echoes throughout: “Don’t get tired and depressed, my dearest Dietrich, it won’t be much longer now.”

Maria von Wedemeyer entrusted this collection of letters to her sister, Ruth-Alice von Bismarck, just before her death in 1977. For years before that, von Wedemeyer would not allow the letters to be published. Eberhard Bethge, Bonhoeffer’s close friend and biographer, wrote in the postscript: “I had resigned myself to never seeing this correspondence.”

by

Post by Diane Reynolds:

The people closest to Dietrich Bonhoeffer weren’t there when he died at Flossenbürg concentration camp, but one he was probably thinking of was his twin sister Sabine.

Bonhoeffer, who would become famous for both his theological writings and his life resisting Hitler, had a very wide acquaintance and many friends. He was part of the interwar trans-European elite and knew almost everybody. He had by all accounts, a self-assurance and a perfect command of manners that made him welcome in the highest echelons of society. He performed the role of a man in charge.

Yet what surprised me as I researched Bonhoeffer was the extent to which women populated his innermost circle of intimacy. For example, in a letter to Bethge, Bonhoeffer wrote that Bethge and Sabine, his twin, were the two to whom he felt, “in contrast to . . . other people … a remarkable sense of closeness.

I discovered (common, I learned in the German biographical tradition) that a male perspective on Bonhoeffer dominates the discourse, best typified by Eberhard Bethge’s mammoth biography. Thus, I began my book on Bonhoeffer and women, called The Doubled Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, to reinsert women more fully back into Bonhoeffer’s life story. In a very real sense, I wrote the book that wasn’t in my library. (For details on a drawing for a free copy of the book, see above.)

Women have often been downplayed in Bonhoeffer’s story. Not entirely, of course, but strange omissions occur. For example, there is no published photo of Elisabeth Zinn, who more than one writer, including Eric Metaxas in his bestselling Bonhoeffer biography, calls Bonhoeffer’s fiancée. (I have a photo of her in my book thanks to the generosity of Zinn’s daughter, Aleida Assman.) And, in another example, the story of his relationship with his fiancée, Maria von Wedermeyer, has been routinely misrepresented: Maria’s story has become part of what filmmaker Laura Pointras calls a “locked narrative:” a somewhat distorted story that has been told so often it attains the status of truth.

Women have often been downplayed in Bonhoeffer’s story. Not entirely, of course, but strange omissions occur. For example, there is no published photo of Elisabeth Zinn, who more than one writer, including Eric Metaxas in his bestselling Bonhoeffer biography, calls Bonhoeffer’s fiancée. (I have a photo of her in my book thanks to the generosity of Zinn’s daughter, Aleida Assman.) And, in another example, the story of his relationship with his fiancée, Maria von Wedermeyer, has been routinely misrepresented: Maria’s story has become part of what filmmaker Laura Pointras calls a “locked narrative:” a somewhat distorted story that has been told so often it attains the status of truth.

My book tells—or tries to tell—the true story of the women closest to Bonhoeffer. This seemed important because it was in dialogue with women (as well as men) that Bonhoeffer hammered out his theology. Further, this man for whom the personal was always the theological and the theological always the personal, built up through these women the layers of experience—all-important to him– that helped form his theology.

For this book, I used the letters and memoirs of some of the women in Bonhoeffer’s life. These sources were a species of women’s writing, often with a strong emphasis on the domestic. In my book, I aimed to capture some of the domestic flavor of the women’s writing—and, through narrative nonfiction also to provide a sensory context for life in Weimar and Nazi Germany.

The joy of God goes through the poverty of the manger and the agony of the cross; that is why it is invincible, irrefutable. It does not deny the anguish, when it is there, but finds God in the midst of it, in fact precisely there; it does not deny grave sin but finds forgiveness precisely in this way; it looks death straight in the eye, but it finds life precisely within it.

Those words took on a deeper meaning in December 1943 as Bonhoeffer found himself one of eight hundred prisoners awaiting trial in Berlin’s Tegel military prison.

At this point, Bonhoeffer still hoped he might be released, perhaps even in time to spend Christmas with his family and his nineteen-year-old fiancée Maria von Wedemeyer.

Eighteen times, Maria von Wedemeyer was able to visit her fiancé in Tegel prison, from 24 June 1943 to 23 August 1944. Their engagement was made up of 18 tormenting farewells. These and their letters were all they had, fanning the flame, over and over again, of their longings for a life together. Maria received the poem “The Past” in a letter smuggled out of the prison at the the beginning of June 1944. On 27 June she was with him again in Tegel, and after the failed coup of 20 July 1944 they saw each other one last time, on 23 August.

(Ferdinand Schlingensiepen, Dietrich Bonhoeffer 1906-1945: Martyr, Thinker, Man of Resistance, 347-348).

He had to admit to himself that “nothing is more tormenting than one’s longing”; and this torment was what lay behind his poem, “The Past”, written immediately after a visit from his fiancée.

You left, beloved bliss and pain so hard to love.

What shall I call you? Life, Anguish, Ecstasy,

my Heart, of my own self a part – the past?

The door slammed shut and locked,

I hear your steps depart, resound, then slowly fade.

What remains for me? Joy, torment, longing?

I know just this. You left – and all is past.

(Ferdinand Schlingensiepen, Dietrich Bonhoeffer 1906-1945: Martyr, Thinker, Man of Resistance, 345-346).

Recent Comments